Representation making difference

Samantha C.W. O’Sullivan didn’t know she wanted to be a physicist when she first arrived on campus. She liked the subject, but the Adams House senior wasn’t sure of what she might be able to do with a physics degree and couldn’t quite picture herself as an academic.

Then she got to know Harvard physicist Jenny Hoffman, Clowes Professor of Science, who opened her eyes to the many possibilities in physics as her first-year adviser. Now O’Sullivan will graduate in May with a degree in physics and a plan to continue her studies at Oxford in the fall as a Rhodes Scholar. She’s grateful that those early conversations set her on a path as a researcher in condensed-matter physics, and that it was another woman who helped get her there.

“That was so powerful,” said O’Sullivan. “She was my first idea of what a physicist is. It really instilled in me an idea of ‘Oh, this can be me as well.’”

O’Sullivan, Maya Burhanpurkar, and Elizabeth Guo, also from the Department of Physics, were awarded U.S. Rhodes Scholarships earlier this academic year. All three women of color said they’d been inspired and guided by faculty like Hoffman, Assistant Professor of Physics Julia Mundy, Associate Professor Cora Dvorkin, and Melissa Franklin, the Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics, who in 1992 became the first woman to receive tenure in the department.

“It makes the department, the field so much more welcoming and shows you what’s possible,” said Rhodes winner Maya Burhanpurkar about women faculty in the Physics Department.

File photo by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

The three note that these professors not only work in a field traditionally dominated by men (at Harvard only a third of the concentrators identify as female) but have become leaders in it. And they demonstrate why representation matters.

“Having those people to not only look up to but when they also agreed to mentor you and guide you through the process of doing research makes it so much easier,” said Burhanpurkar, who graduated in November. “It makes the department, the field so much more welcoming and shows you what’s possible.”

O’Sullivan put it this way: “You can really only be what you know exists.”

The Washington, D.C., native, for example, worked in Hoffman’s lab researching the atomic structure of high-temperature superconductors and took courses in condensed-matter physics from professors like Mundy, who recently won the 2022 Sloan Research Fellowship, one of the most prestigious awards available to young researchers. Learning about the many deep questions and mysteries in these fields led to an interest in this specific area of physics that she wants to explore further.

O’Sullivan, who did a joint concentration in physics and African American studies, said she’ll be joining an experimental condensed-matter physics lab at Oxford, continuing the type of work she started with Hoffman and Mundy.

“I’m following in their footsteps professionally, in a way,” O’Sullivan said.

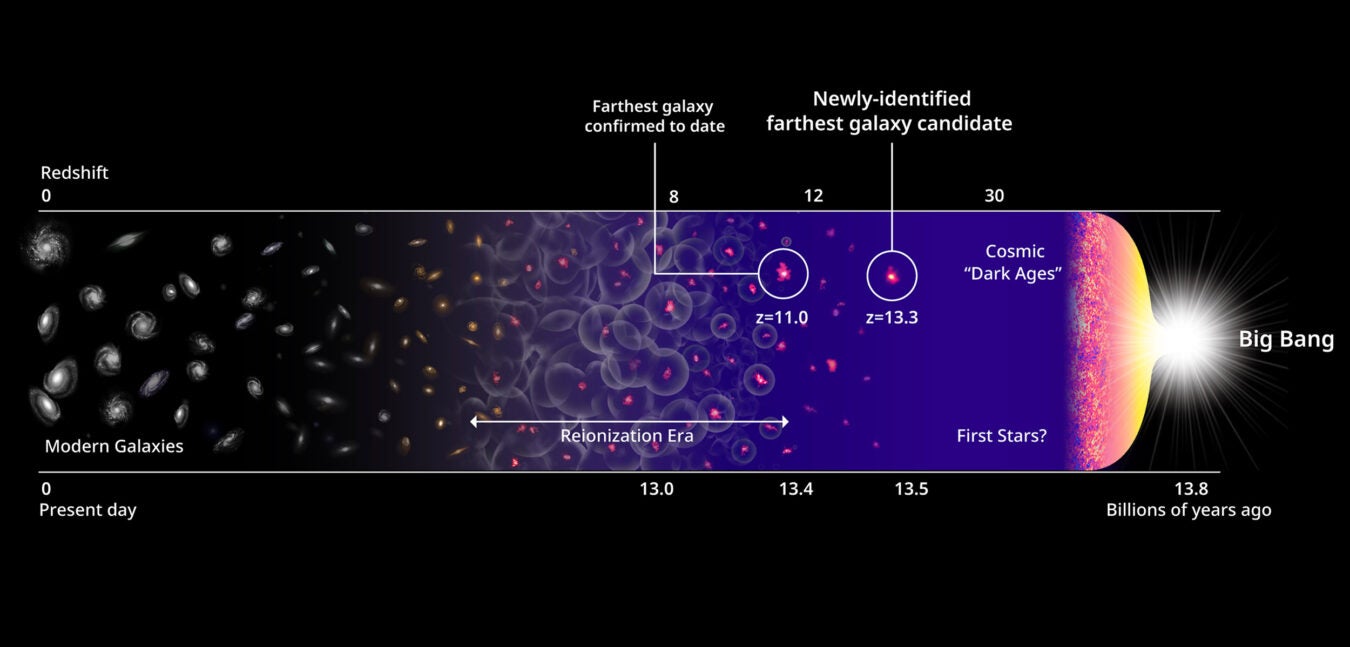

Burhanpurkar, a former Quincy resident from Ontario, Canada, said Dvorkin’s dark-matter research group was the first group she worked in that was run by a woman. She met Dvorkin while taking her graduate-level cosmology course during fall 2019 and later joined her lab. Burhanpurkar was no stranger to physics research, having worked in other labs at Harvard and in Canada, but this was a welcome change because in the field of theoretical physics there aren’t too many women.

The trio also spoke about the ways various professors taught them to expand beyond physics and pursue other endeavors, whether they were academic, professional, or personal (like Hoffman, who moonlights as a marathon runner). Burhanpurkar singled out computer science professor Cynthia Dwork, along with Dvorkin.

Dvorkin “encouraged me to look into applying new research ideas to problems in cosmology that hadn’t previously been applied to physics and pursue them, and she was encouraging of my entrepreneurship,” said Burhanpurkar, who went on to co-found Adventus Robotics, an autonomous robotics startup specializing in self-driving wheelchairs for hospitals and consumers in 2020. “She really just went above and beyond the requirements of supervising an undergraduate on a research project.”

Guo, a Cabot House resident from Plano, Texas, said the impact of the female faculty she worked with will have ripple effects for years. It encouraged her to pay it forward.

“I’ve been trying to do what these women have done for me,” said Guo, who worked in the Hoffman lab beginning her sophomore year, researching quantum materials and their transitions.

Guo helped restart the undergraduate chapter of the Women in Physics organization in the summer of 2019 and, during her junior and senior year, served as its chair. The organization helps support female students and postdoctoral researchers in the department through mentoring, workshops, and community building events — often partnering with Hoffman, Mundy, Dvorkin, and Franklin.

Guo has helped put together informal chats where undergraduates can meet with female physicists over pastries, study breaks so students can work together in small groups, and, during remote learning, a virtual lab fair to help students connect with research groups.

At Oxford, Guo will be seeking a way to merge her love of science with her interests in law. She said the group has become a welcoming safe space for the department’s undergraduate female students. She recalled a recent conversation she had with a younger member of the department.

“She was telling me how she was really grateful for this group just because she had people she could talk to — a group of women whom she could reach out to and see that they had made their way through this department and that she could do the same,” Guo said.

O’Sullivan and Burhanpurkar have also worked to help make the College feel more welcoming to underrepresented students. O’Sullivan started and led the Generational African American Students Association, which aims to foster community among Harvard College students who identify as Generational African Americans, the larger Black community, and Harvard, as well as raise awareness and spark change on issues surrounding the legacy of slavery.

Burhanpurkar, served as a board member for the undergraduate Women in Physics society and as Harvard’s undergraduate representative to the American Physical Society Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity Alliance. She tutored women in physics for two years through the Bureau of Study Counsel and as co-president of the Society of Physics Students she restarted the mentorship program for younger physics concentrators.

The women hope their efforts — and those of faculty who routinely take part in outreach to increase diversity in the field — continue to pay off because of the importance of growing the field.

“I want to make sure that having survived some painful experiences as a junior faculty that I can do some good and prevent other people from having some of those experiences, too,” said Hoffman.

Mundy, who studied as an undergraduate at Harvard, working in Hoffman’s lab, and Franklin, the academic adviser for all three students (and even for Hoffman when she was a College student), said there has been much headway in improving things for women in physics. This Rhodes trio is part of the proof.

“I’m just lucky that I was there,” said Franklin. “The thing about these three is that they’re just so smart and so good at physics. I kind of wish I was as good as they were. Now, I’m thinking maybe I’ll just follow these women and do whatever they’re going to do,” she said, smiling.

Dvorkin agreed.

“My advice [to young women setting out in physics] is to follow their passion, to not be afraid of doing what they like,” Dvorkin said. “The field is changing; it’s improving; and they’re part of this of this improvement, so keep going and keep doing it for yourself and for future generations.”