People around world tend to talk to babies in higher voice

If you’ve ever talked to a baby, you’ve likely raised your pitch, made silly sounds, or used a sing-song voice. You’re not alone.

In a landmark study spanning six continents, researchers affiliated with the Music Lab found striking consistencies in the ways adults spoke and sang to infants. The findings, published this week in Nature Human Behaviour, point to possible common functions of certain kinds of speech and song patterns for infant development and parent-child bonding.

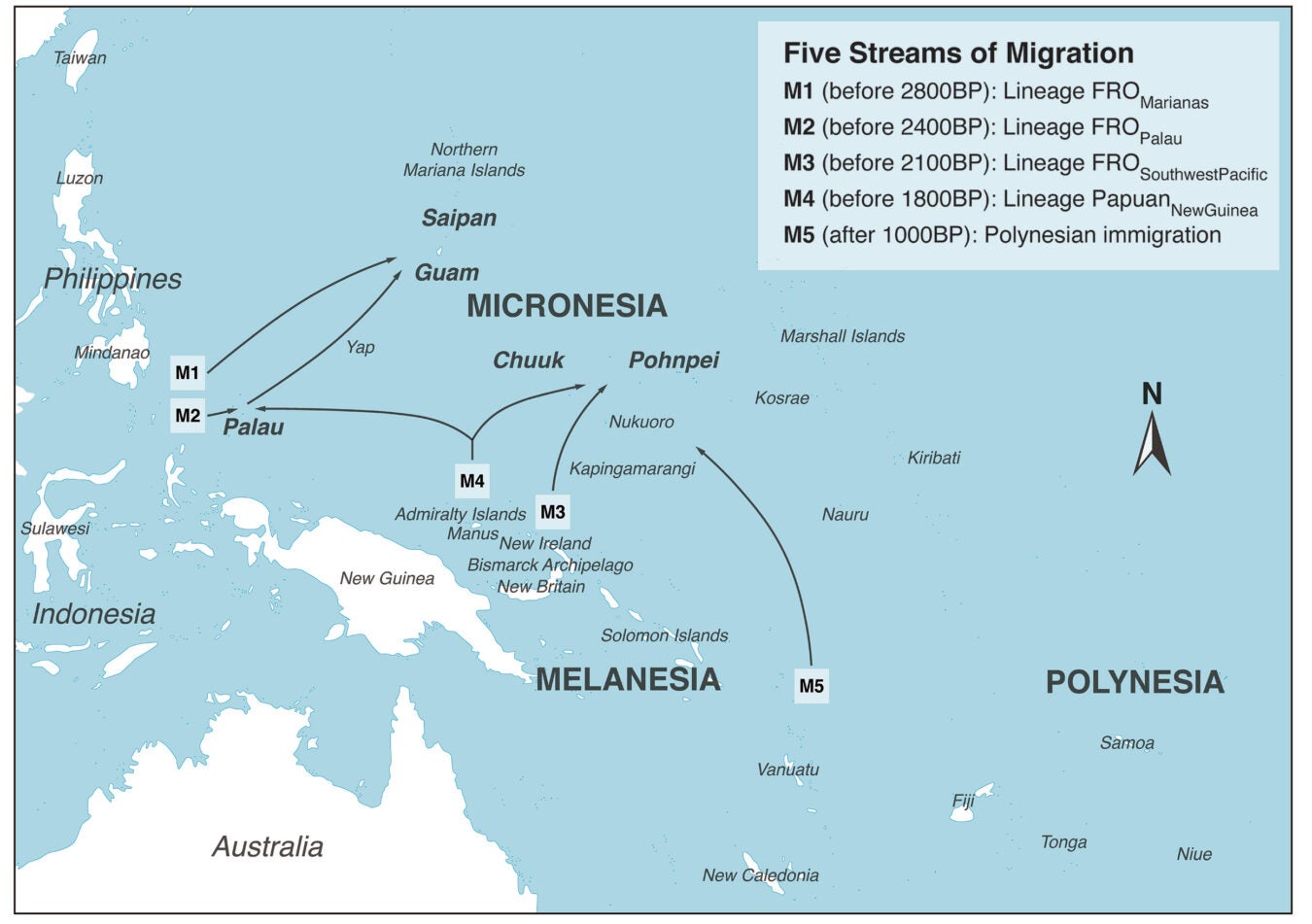

Over a period of three years, researchers coordinated the collection of 1,615 recordings from 21 cultures with varying degrees of connectedness to the rest of the world. From an urban English-speaking environment in San Diego to a Hadza hunter-gatherer society in East Africa, adults changed their speech patterns when interacting with infants. No previous study has compared infant-directed vocalizations across such a wide range of cultures.

“For about as long as people have been studying parents and babies, psychologists have theorized that there are special kinds of vocalizations for babies, but it’s difficult to study that trend in diverse groups of people all over the world,” said Samuel Mehr, who led the project as director of the Music Lab and a Harvard research associate before taking a new role as a senior scientist at Yale’s Haskins Laboratories. “Because of this big international collaboration, we were able to test this question rigorously in many different sites around the world.”

Who's listening? Adult or infant?

In one of the clips, the speaker from Tanzania is speaking to an infant. Can you guess which one based on voice acoustics alone? Answer below. (Clips courtesy of The Music Lab)

First clip is adult-directed; second, infant-directed speech.

Listen to more recordings at The Music Lab.

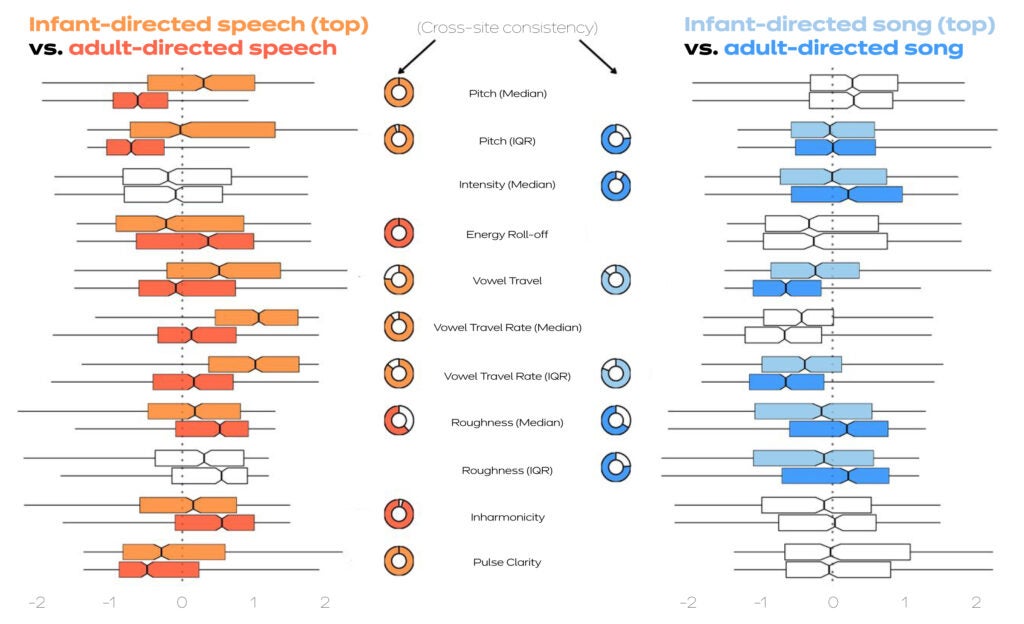

Global consistencies in infant-directed speech included higher pitch and increased pitch range. Other features that appeared many times in the recordings were contrasting vowels (like emphasizing a long “e” and a short “e” in the same word) and pulse clarity (using a musical voice). When the researchers analyzed singing, they noticed consistent changes in tempo and timbre.

The group trained a machine-learning model to use features like pitch and loudness to guess whether a recording was infant-directed or adult-directed. The model was largely accurate in its determination across the 21 societies and strengthened the case for global consistencies, according to Courtney Hilton, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Psychology and a co-first author on the paper.

“Our study provides the strongest test yet of whether there are acoustic regularities in infant-directed vocalizations across cultures,” Hilton said. “It is also really the first to convincingly address this question in both speech and song simultaneously. The consistencies in vocal features offer a really tantalizing clue for a link between infant-care practices and distinctive aspects of our human psychology relating to music and sociality.”

This research builds on earlier studies showing that lullabies and altered speech patterns can have a soothing effect on infants, as well as animal findings demonstrating the clear function of vocalizations such as sounding the alarm for an approaching predator or signaling friendliness and approachability.

“When we were selecting the features with which to look at infant-directed song and speech, we specifically appealed to some baseline bioacoustic principles that can be held constant not only in humans, but across different animals,” said Cody J. Moser, a co-first author on the paper, doctoral candidate at the University of California Merced, and a visiting student in Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “Things about the way that we alter our pitch toward our infants might have their roots in ways that other animals communicate with each other.”

A secondary part of the study involved members of the public trying to identify whether a vocalization was infant-directed or adult-directed. More than 50,000 English speakers with fluency in 199 languages hailing from 187 countries participated in that portion of the study. Most were accurate in their assessments regardless of their native language or culture. This aspect of the research confirmed that people can pick up on the acoustic markers of infant-directed speech and song, even if they don’t understand the words or cultural references.

How people alter their voices when speaking to infants

The researchers trained a machine learning model to analyze the extent to which adults altered their voices when speaking or singing to infants. The figure shows that adult median pitch was heightened when they spoke to infants as compared to adults (left column, top measurement), but remained largely the same during song (right column).

Read the full study.

Mehr said this “citizen science” approach was invaluable to the researchers.

“The method we used for this paper — that allowed us to get 50,000 people to tell us if they thought a certain song was for a baby or for an adult — is the same method that we could use to understand the trajectory of music perception ability across a person’s lifespan, or whether people hear structure in music the same way depending on the type of language they speak,” he said. “The citizen science method is an innovation that many psychologists are excited about.”

The findings show striking parallels among cultures when it comes to talking and singing to infants, but Moser warned that the similarities shouldn’t be understood as truly universal features.

“We’re not trying to claim that all societies have infant-directed song or infant-directed speech, but we do now know that when people do tend to sing to their infants or speak to their infants, they tend to do it in the same way,” around the world, he said. “That is very interesting and a new finding.”

“There is, of course, a lot of variation and cultural influence in this practice, but we were also finding commonalities hinting at roots in our shared biology,” added Hilton. “In this study, we were trying to uncover these hidden parts of our minds that shape our everyday behavior and experiences.”