Climate change drove reptile evolution

Just over 250 million years ago, during the end of the Permian period and the start of the Triassic, reptiles had one heck of a coming-out party.

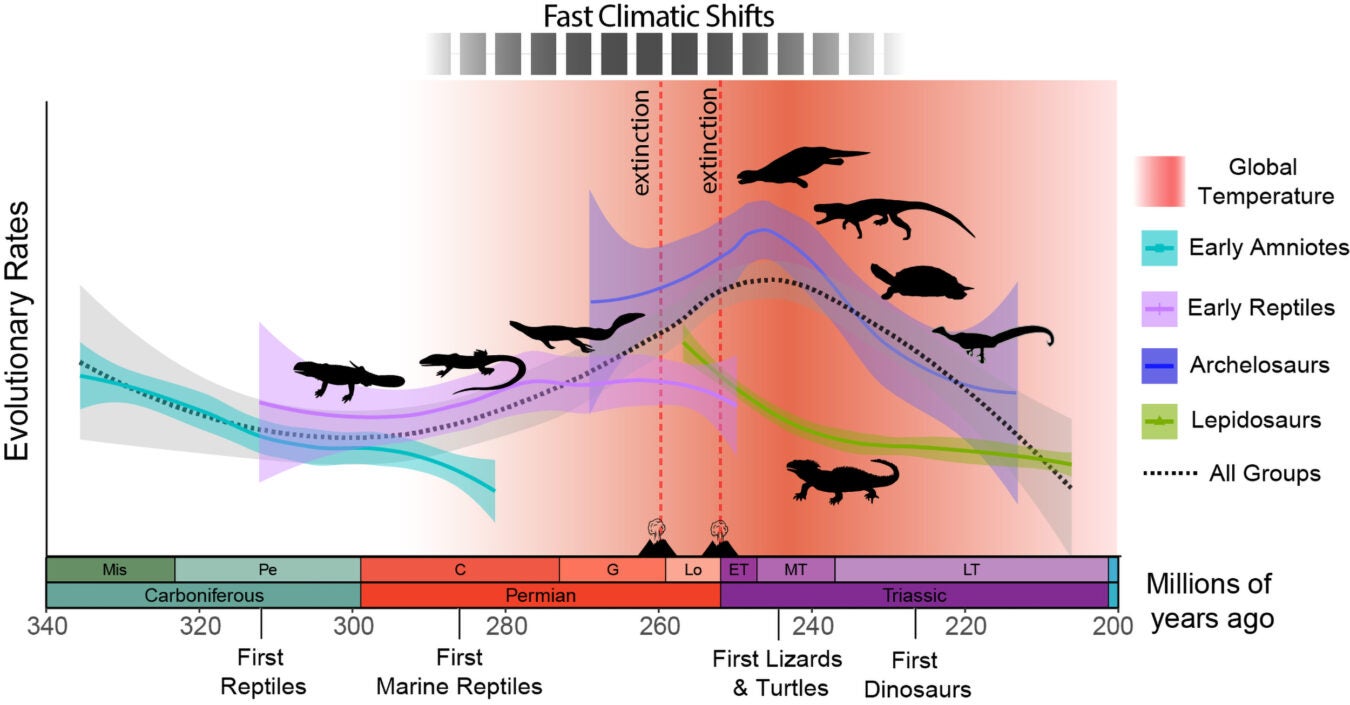

Their numbers and rates of diversity surged, leading to a dizzying variety of abilities, body types, and traits and helping to firmly establish them as one of the most successful animal groups the Earth has ever seen. For years scientists attributed that success largely to luck: Two of the biggest mass-extinction events (around 261 and 252 million years ago) in the history of the planet wiped out much of their competition.

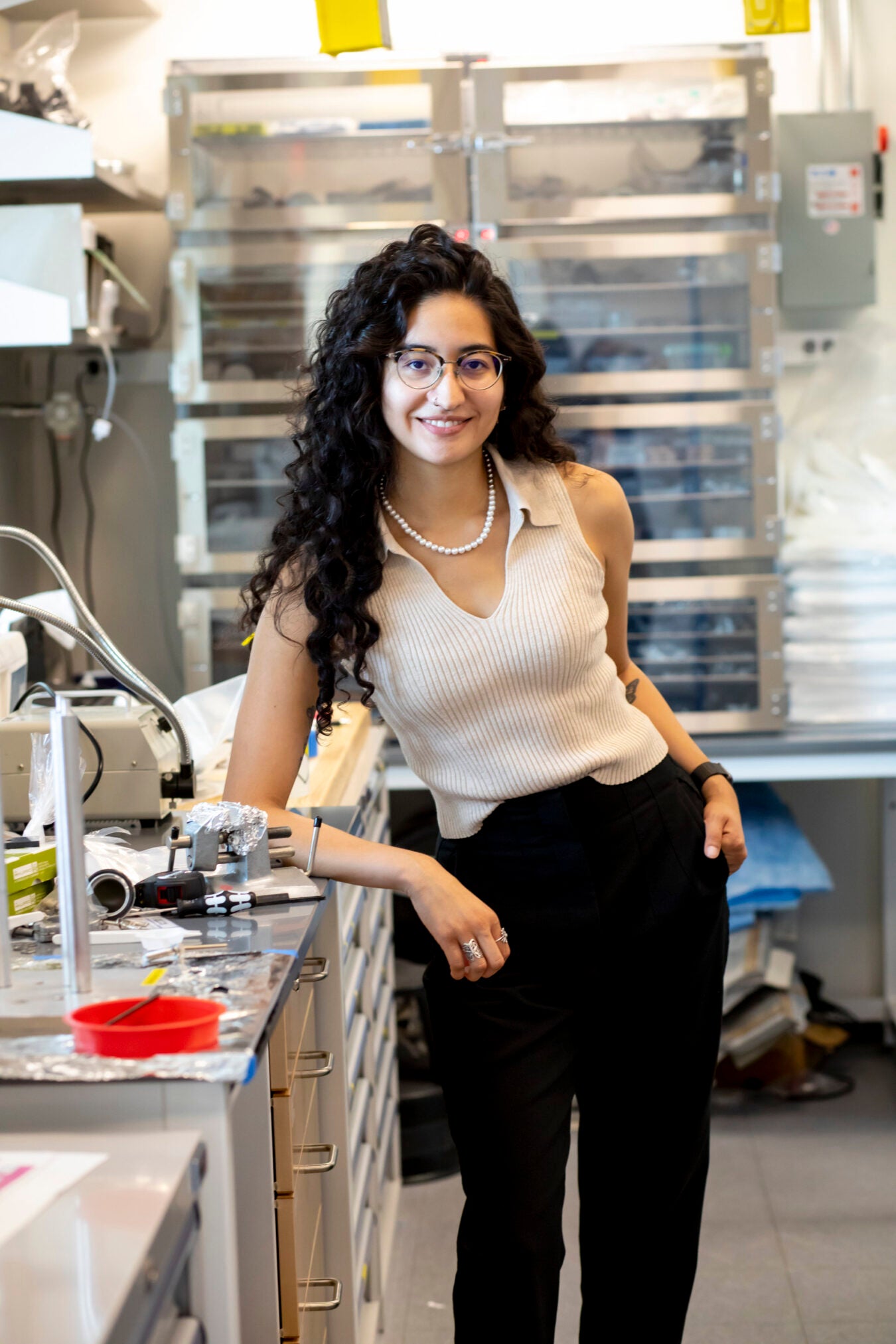

But a new Harvard-led study has added a second major factor to the reptile success story after tracing how the bodies of ancient reptiles evolved in ways that were evolutionarily advantageous amid millions of years of climate change. In fact Harvard paleontologist Stephanie E. Pierce’s lab found that the morphological evolution and diversification seen in early reptiles actually started years before the mass-extinction events took place and were driven by rising global temperatures.

“We are suggesting that we have two major factors at play — not just this open ecological opportunity that has always been thought by several scientists — but also something that nobody had previously come up with, which is that climate change actually directly triggered the adaptive response of reptiles to help build this vast array of new body plans and the explosion of groups that we see in the Triassic,” said Tiago R. Simões, a postdoctoral fellow in the Pierce lab and lead author on the study.

“Basically, [rising global temperatures] triggered all these different morphological experiments — some that worked quite well and survived for millions of years up to this day, and some others that basically vanished a few million years later,” Simões added.

Evolutionary response from reptiles to global warming and fast climate changes.

Tiago Simoes

In the paper, published Friday in Science Advances, the researchers lay out the anatomical changes that took place in many reptile groups, including the forerunners of crocodiles and dinosaurs, concentrated between 260 to 230 million years ago.

The study provides a close look at how a large group of organisms evolved because of climate change, which is especially pertinent today amid rising global temperatures. In fact, the rate of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere today is about nine times that seen in the period that culminated 252 million years ago in the biggest climate-change-driven mass extinction ever: the Permian-Triassic mass extinction.

“Major shifts in global temperature can have dramatic and varying impacts on biodiversity,” said Pierce, Thomas D. Cabot Associate Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology in the Museum of Comparative Zoology. “Here we show that rising temperatures during the Permian-Triassic led to the extinction of many animals, including many of the ancestors of mammals, but also sparked the explosive evolution of others, especially the reptiles that went on to dominate the Triassic period.”

The study involved nearly eight years of data collection along with loads of camerawork, CT scanning, and passport stamps as Simões traveled to more than 20 countries and 50 different museums to take scans and snapshots of more than 1,000 reptilian fossils.

The researchers created an expansive data set that was analyzed with state-of-the-art statistical methods to produce a diagram called an evolutionary time tree. That helped researchers see how early reptiles were related to each other, when their lineages first originated, and how fast they were evolving. They then overlaid it with global temperature data from millions of years ago.

Diversification of reptile body plans started about 30 million years before the Permian-Triassic extinction, making it clear these changes weren’t triggered by the event, as previously thought. The extinction events did help put them in gear though.

The data set also showed that rises in global temperatures, which started about 270 million years ago and lasted until at least 240 million years ago, were followed by rapid body changes in most reptile lineages. For instance, some of the larger cold-blooded animals evolved to become smaller, allowing them to cool down easier; others evolved to life in water. The latter group included some ill-fated reptiles that would eventually become extinct, such as a giant, long-necked marine reptile (like the modern conception of a Loch Ness monster); a tiny, chameleon-like creature with a bird-like skull and beak; and a gliding reptile resembling a gecko with wings. It also includes the ancestors of reptiles that still exist today, such as turtles and crocodiles.

Smaller reptiles, which gave rise to the first lizards and tuataras, traveled a different path than their larger reptile brethren. Their evolutionary rates slowed down and stabilized in response to the rising temperatures. The researchers believe it was because the small-bodied reptiles were already better adapted to rapidly rising temperatures.

The researchers say they are planning to expand on this work investigating the impact of environmental catastrophes on evolution of organisms with abundant modern diversity, such as the major groups of lizards and snakes.