DNA shows poorly understood empire was multiethnic with strong female leadership

Most of what is known about the Xiongnu people comes from their enemies.

“If you do an online image search, most of what you find are brutal battle scenes,” said Christina Warinner, associate professor of anthropology and an expert in biomolecular archaeology. “It’s all very masculine, very violent.”

In research published earlier this month in Science Advances, Warinner worked with a team of archaeologists and geneticists to paint a fuller picture of the world’s first nomadic empire. What they found was a multiethnic society, reflecting nearly all the diversity that existed in Eurasia 2,000 years ago. The researchers also confirmed contemporaneous reports regarding the high status and political power of Xiongnu women.

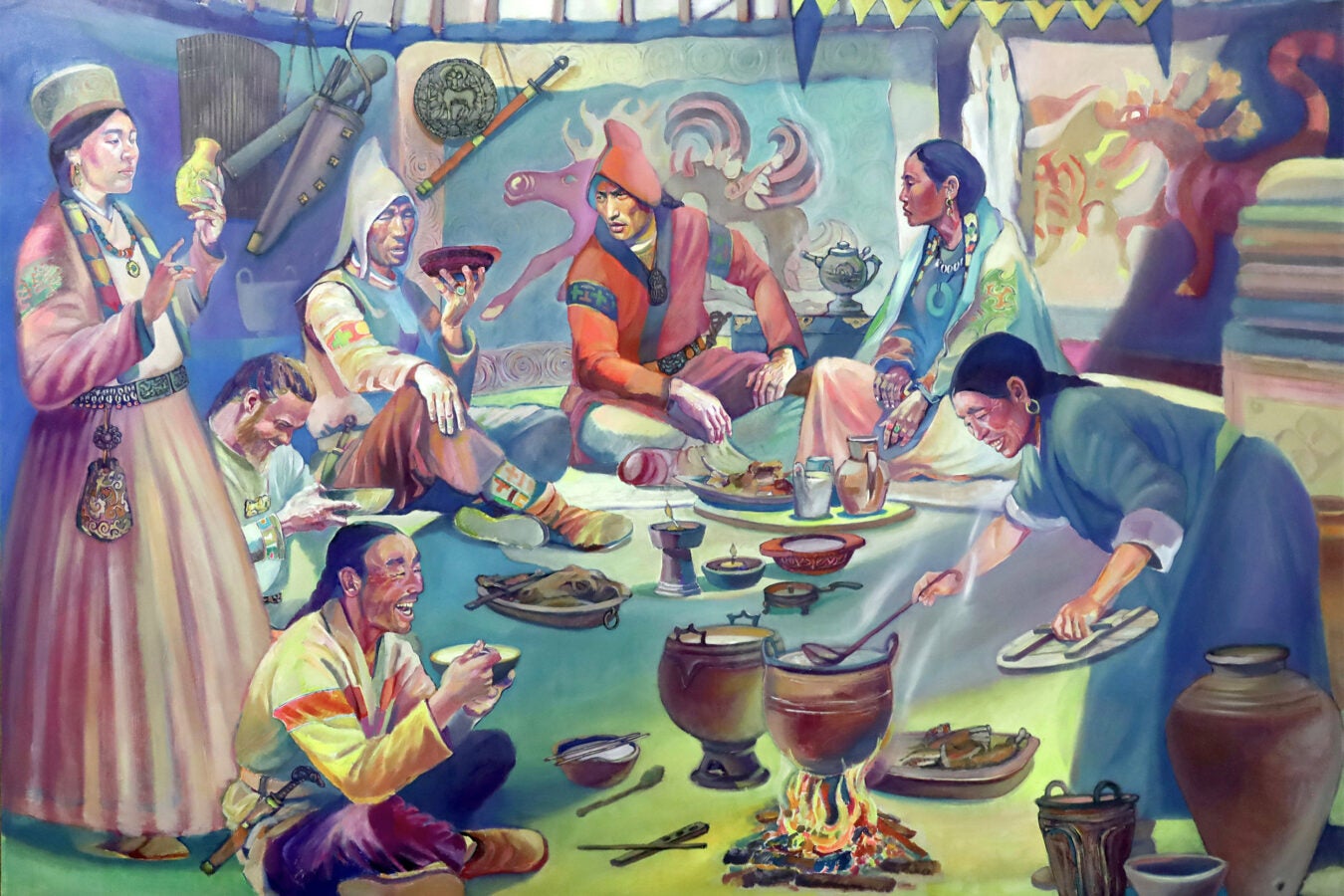

The co-authors commissioned an artist to depict their findings about the Xiongnu.

Illustration courtesy of Christina Warinner

“We set out to integrate genetics and archaeology in a new way,” noted Warinner, who is also the Sally Starling Seaver Associate Professor at Harvard Radcliffe Institute. “One of the most exciting things about the study is offering a fresh perspective on this much-maligned population.”

The Xiongnu, contemporaries of the peoples of ancient Egypt and Rome, dominated the Mongolian steppe from about 200 B.C. to 100 A.D. These horseback nomads proved innovative in warfare, but historians know little about the inner workings of their culture because the Xiongnu never developed a formal writing system. “Most of what we know comes from the Han Dynasty of Imperial China,” Warinner said. “They were major rivals of the Xiongnu, and they wrote about their wars and skirmishes along the border.”

In fact, the Great Wall was built as a barrier to mounted Xiongnu warriors.

Also detailed in historic documents are the Xiongnu’s powerful women. “That was another reason Imperial China didn’t like them,” Warinner quipped.

Physical evidence of these claims has been hard to come by. “In most places in the world, the archaeological record abounds in residential domestic debris,” Warinner said. “The problem with mobile societies is they don’t stay anywhere long enough to build up that kind of archaeological record.”

What the Xiongnu did leave behind are vast mortuary complexes, elaborately built from stone and visible from miles away — they even show up on satellite imagery. It’s been well over 10 years since archaeologists Jamsranjav Bayarsaikhan and Bryan K. Miller excavated two such burial sites, located at the western edge of the Xiongnu empire (in Mongolia’s present-day Khovd Province, not far from the border with China). Artifacts recovered there include fine silk, glass beads, and lacquered vessels. “The Xiongnu valued far-flung trade goods,” Warinner said. “They were an early globalizing society.”

Miller subsequently worked with Warinner on an enormous study, published in 2020, that reconstructed the genetic history of Mongolia over a span of 6,000 years. That meant sequencing the DNA of human remains recovered from archaeological sites across the windswept country. “At the time, we only analyzed one or two individuals per site,” said Warinner. “From that, we could tell the Xiongnu were genetically diverse and multiethnic. But we weren’t able to say anything about their gender or social roles or about whether there was a relationship between their genetics and social status.”

Understanding the “internal dynamics” of Xiongnu communities would require a new line of inquiry. As Bayarsaikhan and Miller saw it, this could be accomplished via cross-disciplinary research at the burial sites. With the archaeological work complete, Warinner signed on to lead the genetic lab work while analysis was done by Juhyeon Lee, a Ph.D. candidate with the Department of Biological Sciences at Seoul National University and lead author on the new paper.

Items found at the burial sites: A faience bead depicting the Egyptian god Bes, protector of children; ornamental sun and moon.

In the end, the scientists harvested genome-wide data for 19 individuals, with 17 yielding sufficient human DNA for analysis. “We found that the aristocratic elite tombs were occupied by women,” said Warinner, who went on to list some of the symbolic goods buried with them — a gilded iron belt buckle, horse tack, a wagon, an ornamental sun and moon. “I think what we’re seeing is that as armies of Xiongnu warriors were going out and expanding the empire, elite women were governing the borders,” she said.

As a group, these aristocratic women exhibited the lowest genetic diversity, Warinner added, suggesting that power was concentrated within particular lineages. As for the servants buried around them, they turned out to be a highly diverse group of males, incorporating populations from the empire’s farthest reaches and beyond.

A different pattern was observed with burials of lower-level elites. There, strategic marriages appear to have been used to cement ties to newly incorporated groups. Taken together, the patterns of genetic ancestry and kinship along frontier communities point to the different means by which the Xiongnu grew their multiethnic empire. “Some have proposed that the Xiongnu Empire was made up of a multitude of clans who themselves were fairly homogenous,” Warinner said. “We found that’s not true. They’re genetically diverse even within a single community.”

DNA evidence also complemented archaeological discovery in touching ways. Tween boys were buried with toy-like bows and arrows. A woman was buried with her perinatal infant, both apparently the casualties of childbirth. Around the mother’s neck was a faience bead depicting the Egyptian god Bes, protector of children.

Warinner and her co-authors were so moved by these “intimate snapshots” that they commissioned an artist to capture the project’s findings. The result is a colorful social scene filled with strong women, ethnic diversity, and finery from all over the continent. “For the first time,” Warinner said, “we get to see the Xiongnu as they presented themselves.”