The human brain is a tangled highway of wires emanating from nearly 100 billion neurons, all of which communicate across trillions of junctions called synapses. “Depressingly complex,” Harvard neuroscientist Jeff Lichtman calls it. The only way to understand this highway, says Lichtman, is to create a map.

Lichtman, the Jeremy R. Knowles Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology, has spent several decades generating such maps, and in doing so has pioneered a field known as “connectomics.” His ultimate goal is a whole-mammalian brain map accounting for every neural connection, a so-called “connectome.”

Now, Lichtman and colleagues are embarking on a critical new step of that journey by seeking to capture synapse-level connectome data from a mouse brain at unprecedented clarity and resolution.

Lichtman and partners including Princeton University, MIT, Cambridge University and Johns Hopkins have received $30 million from the National Institutes of Health and an additional $3 million from Harvard and Princeton toward the goal of reconstructing, for the first time, all the neural wiring inside a mouse brain. They’ll prove the feat possible by first imaging a 10 cubic-millimeter region in the mouse hippocampal formation, the portion of the brain responsible for memory consolidation, spatial navigation, and other complex tasks.

Like the Human Genome Project cataloged every human gene and its unique DNA sequence, Lichtman’s connectome, which he has worked on since arriving at Harvard in 2004, would be a comprehensive diagram of every neural connection in the brain.

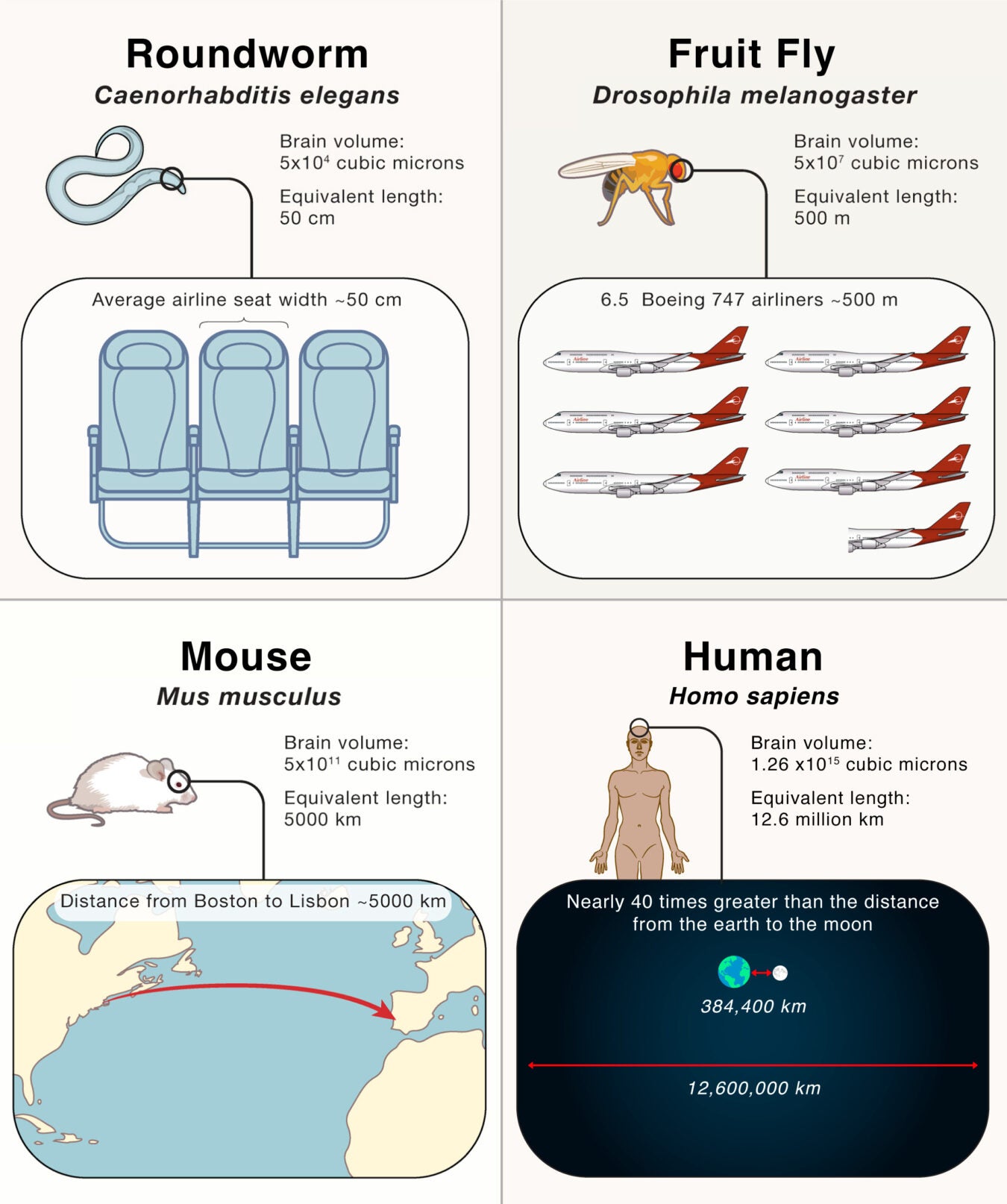

Comparing brain volume from worm to human

Each 1,000 cubic microns of brain volume is schematically represented by a 1 cm. linear distance.

Source: "The Mind of a Mouse," Cell; Jeff W. Lichtman and Viren Jain

Creating a connectome of the human brain could lead to new approaches in diagnosing and treating disorders of the brain, from autism to schizophrenia. Scientists suspect these diseases are “connectopathies” — subtle miswirings that no currently available brain scans can detect.

“Connectomics is the only pathway,” said Lichtman, an affiliate of Harvard’s Center for Brain Science. “If we get to a point where doing a whole mouse brain becomes routine, you could think about doing it in say, animal models of autism. There is this level of understanding about brains that presently doesn’t exist. We know about the outward manifestations of behavior. We know about some of the molecules that are perturbed. But in between, the wiring diagrams, until now, there was no way to see them. Now, there is a way.”

The National Institutes of Health awarded new recipients of the Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® Initiative, or BRAIN Initiative, funding in early September. The Harvard team is being funded through the BRAIN Initiative Connectivity Across Scales network, aimed at developing research capacity and technical capabilities for creating wiring diagrams of whole brains.

The only way to understand the "depressingly complex" human brain is to create a map, says Jeff Lichtman, who has spent decades pioneering work in "connectomics."

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Current techniques lack either the resolution or the ability to scale across and map out large regions of the entire brain, information that is essential for unraveling the mysteries of this incredible organ,” said John Ngai, director of the BRAIN Initiative. “Following years of careful planning and input from the scientific community, BRAIN CONNECTS — which represents our third, large-scale transformative project — aims to develop the tools needed to obtain brain-wide connectivity maps at unprecedented levels of detail and scale.”

The mouse brain is, of course, much smaller than a human’s, but when looking at individual neurons, synaptic vesicles and glial cells, “you can’t tell the difference,” Lichtman said. “At the level of cells and synapses, all mammalian brains are basically the same.”

Given recent advances in computing and data processing, and prior work by Lichtman and others — including Professor Florian Engert in molecular and cell biology — on the brains of zebrafish and fruit flies, achieving a mouse brain map has become more feasible and would serve as an early proving ground for imaging the human brain. Lichtman and colleagues urged collective efforts toward the lofty goal of a mouse brain connectome in a 2020 opinion piece titled “The Mind of a Mouse.”

The researchers will apply biological imaging techniques Lichtman and colleagues have invented over the course of several decades to achieve their goals. For the NIH project, they will employ a two-tiered system. First, two 91-beam scanning electron microscopes, one at Harvard and one at Princeton, will capture images of thin sections of the mouse hippocampal formation. The surface of each section will then be etched away with an ion beam just a few nanometers at a time, and the imaging process will be repeated until the entire volume is viewed. A team at Google Research will computationally extract the resulting wiring diagram with machine learning.

The team expects to generate about 10,000 terabytes of data for their 10-square-millimeter mouse brain section; 50 times that amount of data would be generated for a whole mouse brain. Over the first half of their five-year project, the team expects to generate up to 50 terabytes of data per day.

Lichtman’s team has worked with Google over the last several years on image processing techniques that allow them to make sense of large amounts of data quickly. Engineers led by grant co-investigator Viren Jain will apply artificial intelligence algorithms to these brain images to categorize and color-code nerve cells and synapses. Google will also help publicly share this enormous brain map.

“We plan on using our experience with computational reconstruction and analysis of large-scale electron microscopy data, along with Google’s highly scalable data processing infrastructure, in order to enable mouse connectomics at an unprecedented scale,” said Google’s Jain. “We have worked closely with Jeff’s lab over five years, and this collaboration has been highly successful in pushing the frontiers of data-intensive neuroscience.”

The research is supported by the NIH BRAIN Initiative under award number 1UM1NS132250-01. Lichtman is involved with another BRAIN CONNECTS grant awarded by the NIH, which is led by Professor of Physics Aravinthan D.T. Samuel and is aimed at developing a rapid-imaging strategy for connectomics. More information on other awardees.

Post a Comment